The Waiting is the Hardest Part

Prisoners in a gilded cage waiting on the weather

Many decisions fall onto a continuum with patience on one end and the trap of “perfect becoming the enemy of good” on the other end. A good decision strikes a balance between the two extremes1.

Ocean passages are like this. Patience can give you smooth seas, settled weather, and favorable winds. Waiting too long means you miss good opportunities to get across the ocean. Poor departure decisions are usually the result of not having enough patience, not from waiting too long. I’m working hard to be patient.

Most of the time, it is crew schedules and self-imposed deadlines that cause sailors to run out of patience and leave too early. There is nothing as dangerous as a sailor on a schedule. Sometimes, people just get tired of waiting. “Heck with it. Let’s just go…”

Aviation is similar. “Funerals for pilots are held on sunny days,” my old flight instructor would say. Be patient.

The best storm management tactic is not sailing out into the storm to begin with.

Awash in Weather Data

We are awash in weather data. And weather experts. It can be overwhelming if you don’t have a system and a structured approach to processing and analyzing all of it.

Numerical weather models are at the heart of this planning2. These models are created and run by government and private weather agencies. Most of them run twice a day (they require a lot of computing power). The model output then finds its way into dozens of apps, websites, and tools—including the weather app on your phone.

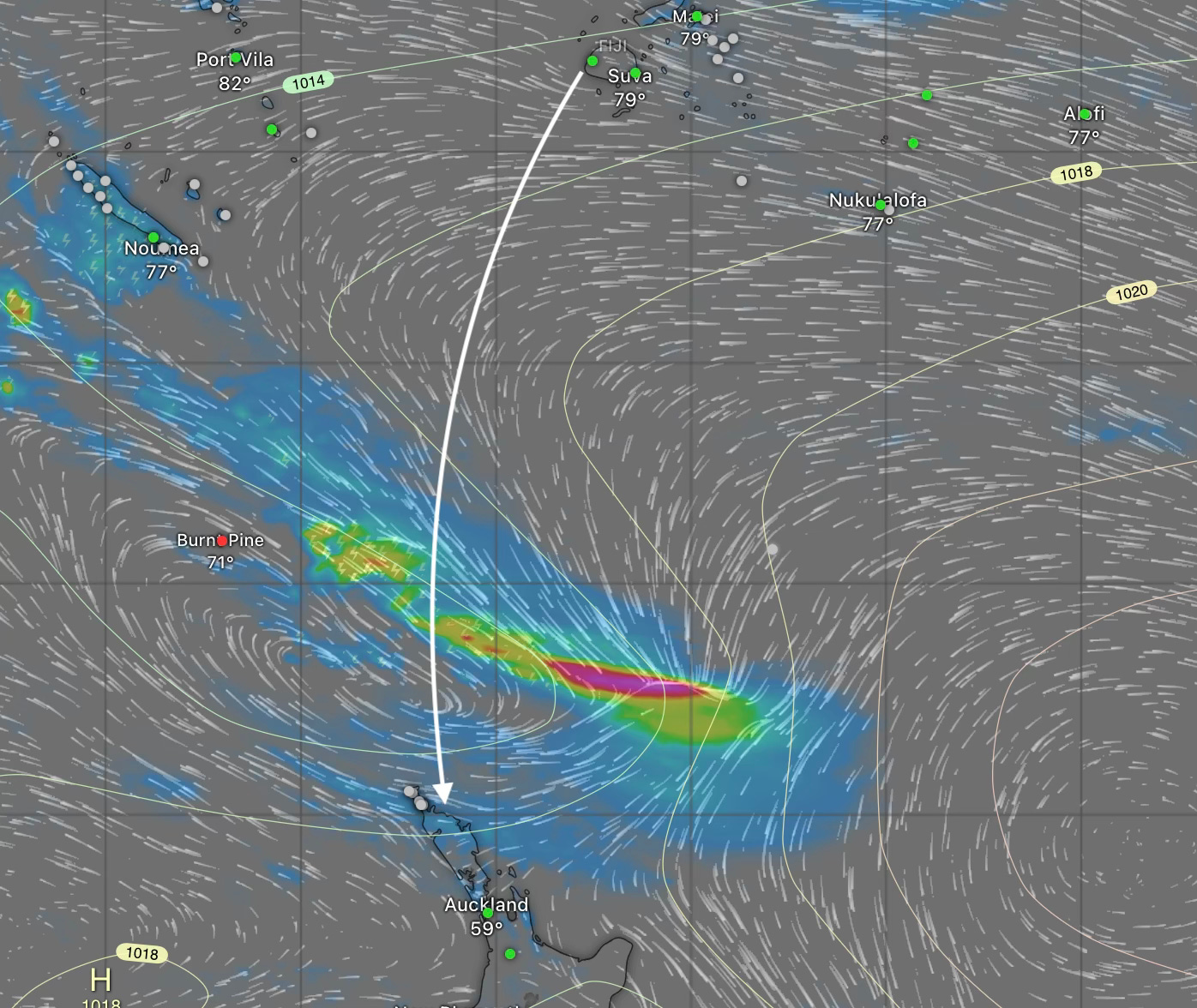

We analyze the outputs twice a day. PredictWind for routing. Windy for big-picture analysis. From those, we come up with a rough hypothesis of when we can leave, when we’d arrive, and the conditions en route. As we settle on a target departure date, we send the ideas to our weather routers for their reaction. They frequently notice risks I don’t see (which is why we hire them). They are pattern-matching based on their years of experience in this region. Otherwise, they have the same models and data we have.

Stan Honey3, arguably the world’s greatest living ocean navigator (and a huge influence on me as a sailor), advises the 8, 6, 3 approach to weather models. Review them 8 days out. Strongly consider them 6 days out. Take them to the bank 3 days out. Beyond 8 days, weather is too dynamic to rely on the models. Three days out, they are very accurate.

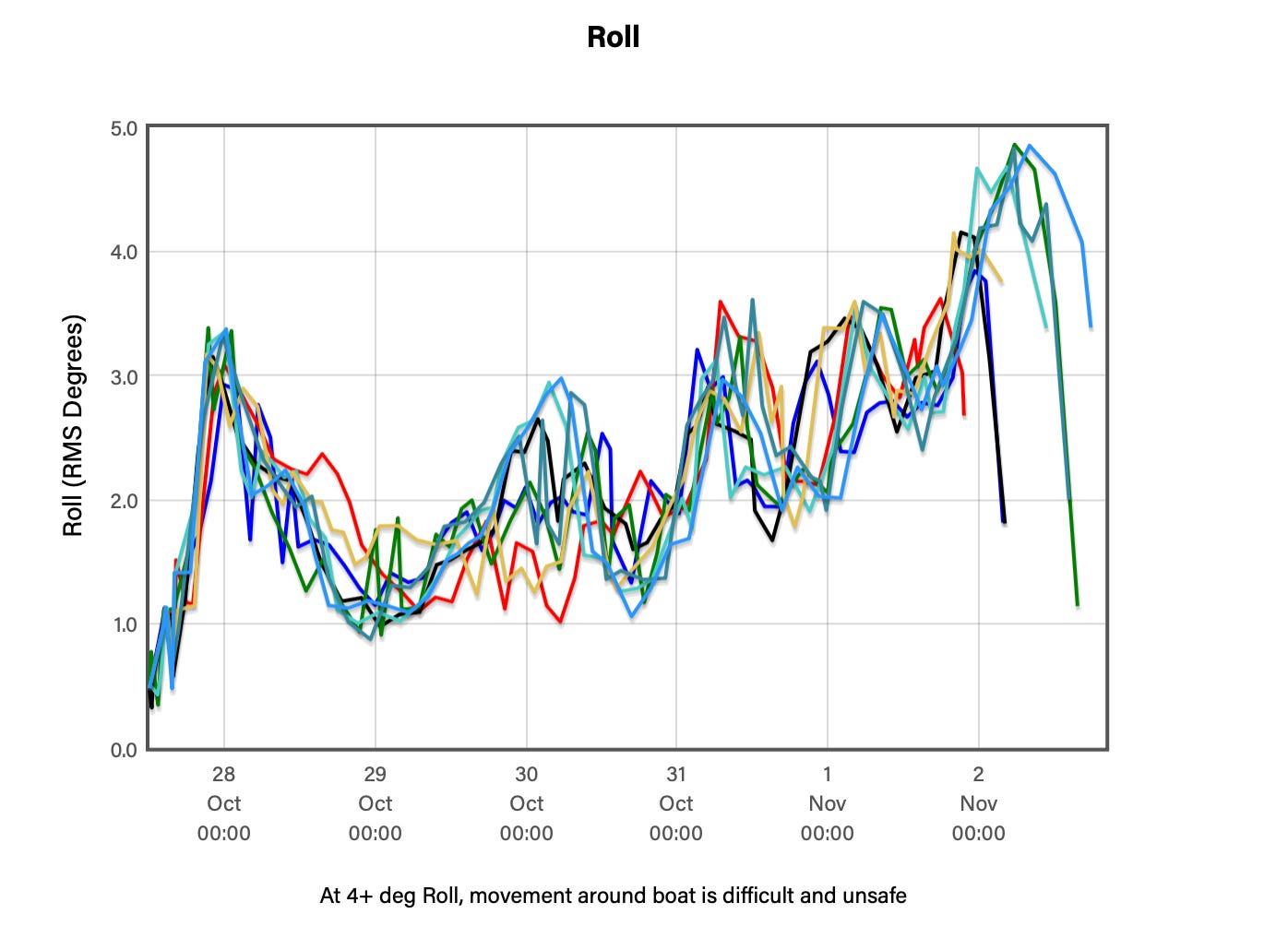

Sea state comes first. When the seas are smooth, anything is possible. When the seas are rough, everything sucks. It’s the seas that break boats and sailors, not the wind. Then we look at the storms. Lightening and squalls. Finally, wind direction. We have enough fuel to motor the entire route, but sailing is way better.

We know what the ideal weather pattern looks like. When it doesn’t shape up, you start squinting your eyes looking for ways to make the current weather work. It’s classic confirmation bias. This is what fellow sailors and weather routers are good for. They call you out on your wishful thinking. Hope is not a strategy.

In ocean racing, the start date is set and rarely changes. In cruising, the start date is whenever you want it to be. You might think cruising sailors have it easier. But sometimes the open-ended nature of cruising is harder to plan than the tightly defined world of ocean racing.

Weather Windows

Many months ago, we picked 19 October as our target departure date. We’d leave on or after that day. As it happened, the 17th was the start of the last weather window (the time needed to complete the route in good weather). We missed that one. We’ve been waiting since. The 22nd? Eh, almost. The 24th? Nope, gale-force winds in New Zealand upon landfall.

My friend Richard arrived on the 18th. My friend Dave, our third crew member, has two refundable tickets from SFO. Each day, he reschedules one of them a few days into the future. This is a good way to reduce schedule-driven impatience. It requires a flexible lifestyle at home, though. Flying in at the last minute lets him keep his business running. And it will leave him more time to enjoy sailing in New Zealand.

Today, it looks like Wednesday the 29th might work. There is a period of settled weather in New Zealand starting around the 2nd of November. That reduces some of the risk in our landfall. We’ll see how it goes.

While we wait, we putter on the boat, knocking out small projects. We clean the bottom and send videos of it to New Zealand’s biosecurity inspectors. We hike around the island and check out the restaurants. And we scuba dive with the local dive shop in the mornings. Not a bad way to wait.

I heard Jeff Bezos talk about decision-making once. He described viewing decisions as “one-way doors” or “two-way doors.” A two-way door decision is one you can change, unwind, and go back to where you were (albeit with some opportunity cost). A one-way door is one where it is very difficult to go back to where you were. He advised making two-way door decisions quickly and one-way door decisions deliberately and with great care. Most ocean passage decisions are one-way doors. It’s hard to turn around and go back. Often the very winds and seas that made you depart are working against you if you go back.

Our core models include the global ECMWF and GFS models. We use regional, mesoscale models like PWE, PWG, and the Australian ACCESS model when looking at conditions close to land. Recently, PredictWind started making two AI-based models available: PWAI, and AIFS. AI models are probabilistic models as opposed to the older deterministic models. Probablistic models are better suited to the kind of risk management we’re doing in passage planning. But they are new and we are all trying to decide what we think about them.

Stan is also in the broadcast hall of fame for inventing the technology that superimposes the yellow first down line on a TV football broadcast.

So much more to “passage planning” than 20 years ago not to mention that being 20 years older has added a large degree of patience to process

Love this perspective. Self-imposed deadlines are truly the trickyest bug to debug.