Passage Planning: Fiji to New Zealand

Finding a safe and comfortable route across 1,100 nautical miles of open ocean

I’ve stopped trying to be right and instead try to be less wrong. If you focus on being right, you can get trapped by confirmation bias. You’ll find evidence to support your conclusions and discard evidence to the contrary. But if you focus on being less wrong, you are more likely to find flaws in your reasoning. You’ll be more willing to change your mind and your plans1.

Weather routing matters because it helps keep the crew and the boat safe. It underpins the trip’s enjoyment. The passage from Fiji to New Zealand is different from the trade wind coconut milk run we’ve been sailing since French Polynesia. Instead of following the trade winds from east to west, we make a hard left turn and sail due south, across the trade winds to New Zealand. We’ll cross 20 degrees of latitude. We’ll plow directly into the southerly swell. We’ll sail through three climate zones2. It’s a demanding stretch of ocean—especially when closing on the New Zealand coast, where the weather systems are dynamic, extreme, and harder to forecast.

Thousands of boats have made this passage. Hundreds do it every year. The strategy for the route is well known. It’s completely new to me, however. I’ve engaged a few experts to help me learn the weather patterns on the route, and studying everything I can find on the subject.

Sailing the Back Side of the High

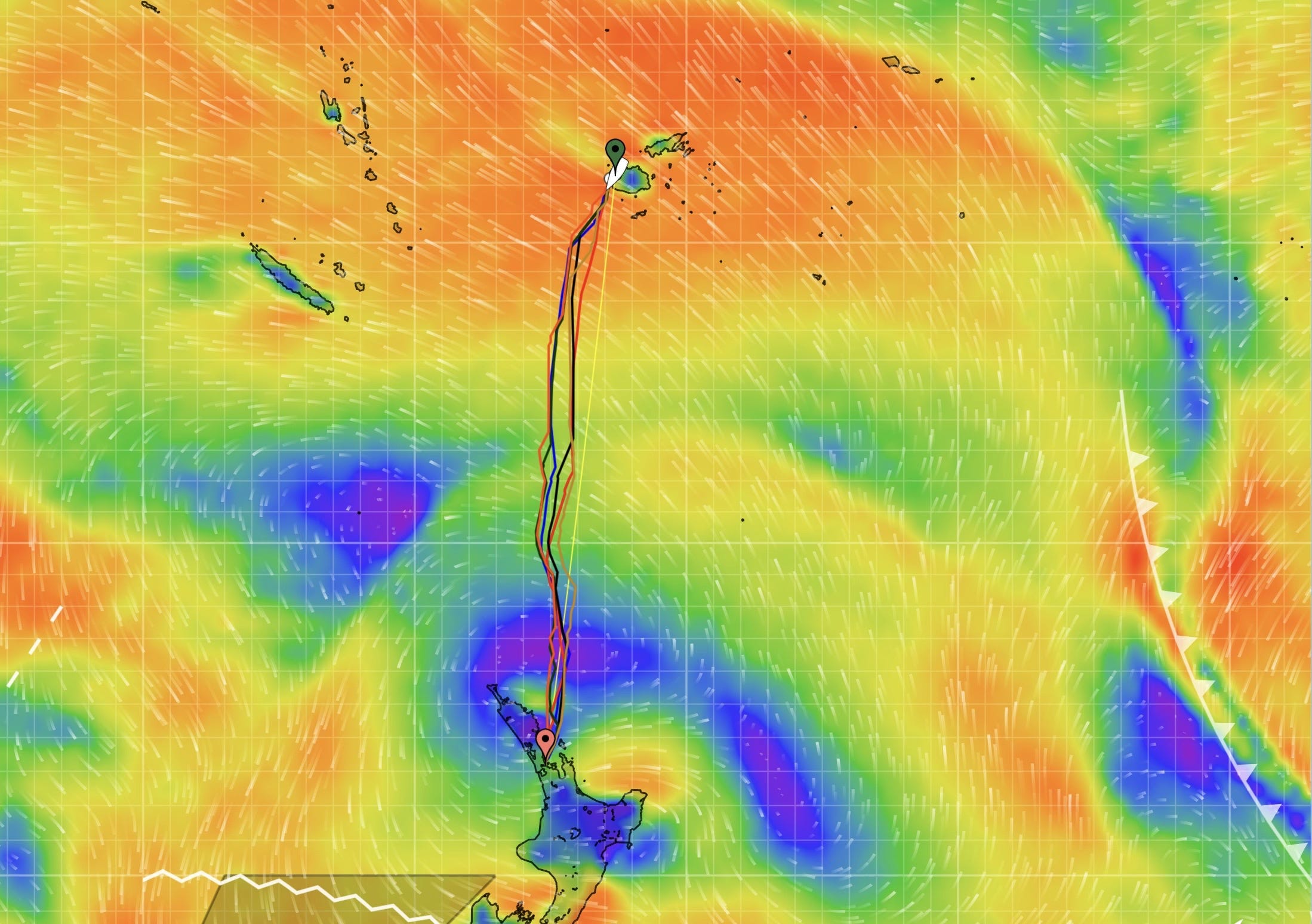

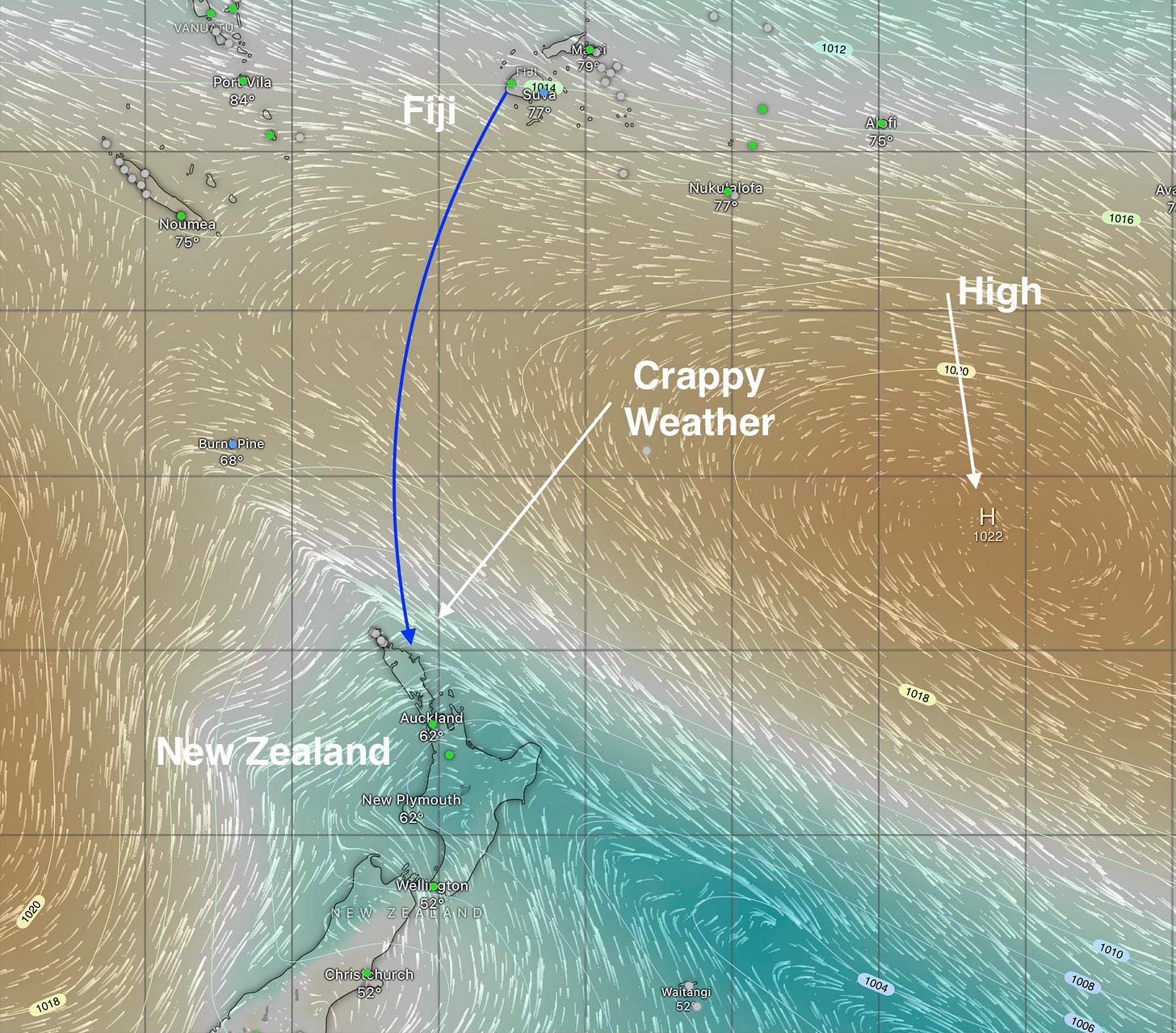

We’ll wait for a moderate high-pressure system (<1025mb) to move from west to east and position itself between Fiji and New Zealand. The wind circulates counterclockwise around the high (in the southern hemisphere). We’ll ride that wind around the high and down to New Zealand as the high moves from east to west.

We need to arrive in New Zealand before the next low-pressure system roars in and creates havoc. And, it’s best to leave a 24-hour margin ahead of that low in case the forecast is inaccurate.

It should take us around six days to get across based on our typical speeds. Maybe a little less. A weather window usually lasts from five to eight days. The key is to pick the right window so that we can get all the way across before the window closes and the next storm descends on New Zealand.

If we can’t get all the way across, we might stop and wait a few hundred miles north and let the low pass by between you and New Zealand. Then, pick up again and finish in good weather. Easier said than done, I’m sure. The temptation to get home is strong. In aviation, we call it “get-there-itis.” It kills a lot of pilots and their passengers.

An Example

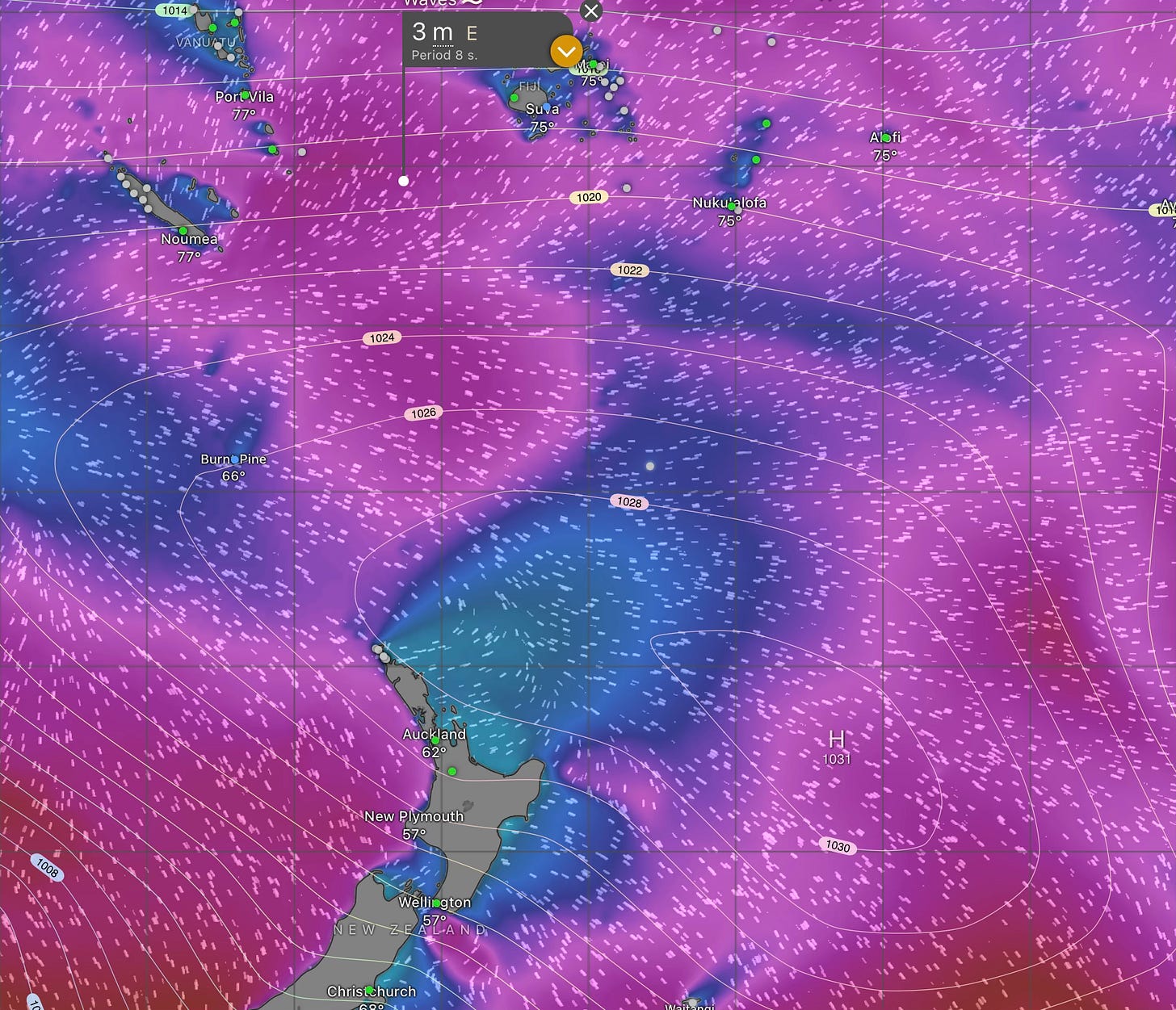

Here is today’s pressure map. You can see the high sitting between Fiji and New Zealand. You might be tempted to go today (assuming your crew was here, you had bought fresh food, made an appointment for your immigration departure clearance, cleaned the bottom, video’d the bottom for NZ bio-security, topped off the fuel and water tanks, and sent your New Zealand arrival documents).

Here is the same high-pressure system six days later. It has moved off to the east and brought the wind around to the north (and somewhat lighter). But not so fast. The window didn’t stay open long enough to get to New Zealand without getting smacked by the next low-pressure system. Maybe next time.

Start With the Sea State

We always start with the sea state. When the seas are calm, anything is possible. When the seas are rough, everything sucks. Despite our obsession with the wind, it’s the sea state that matters most. Broken boats and broken sailors are almost always the result of rough seas, not high winds. Of course, if the wind blows hard enough, long enough, the seas get big.

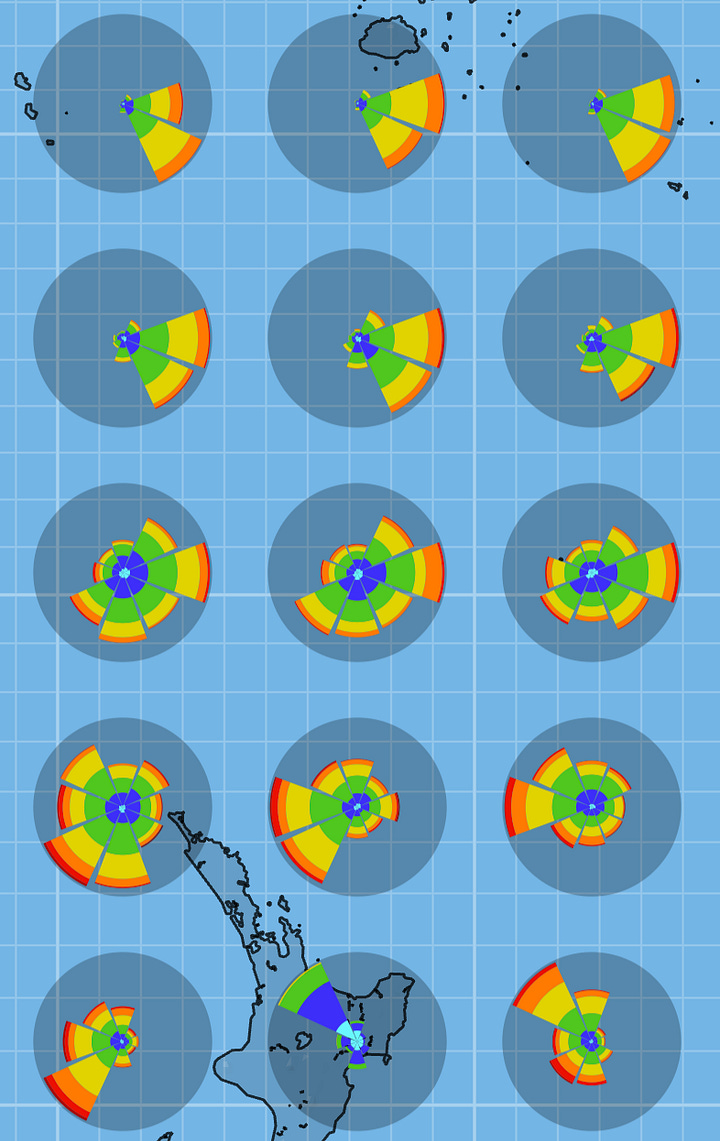

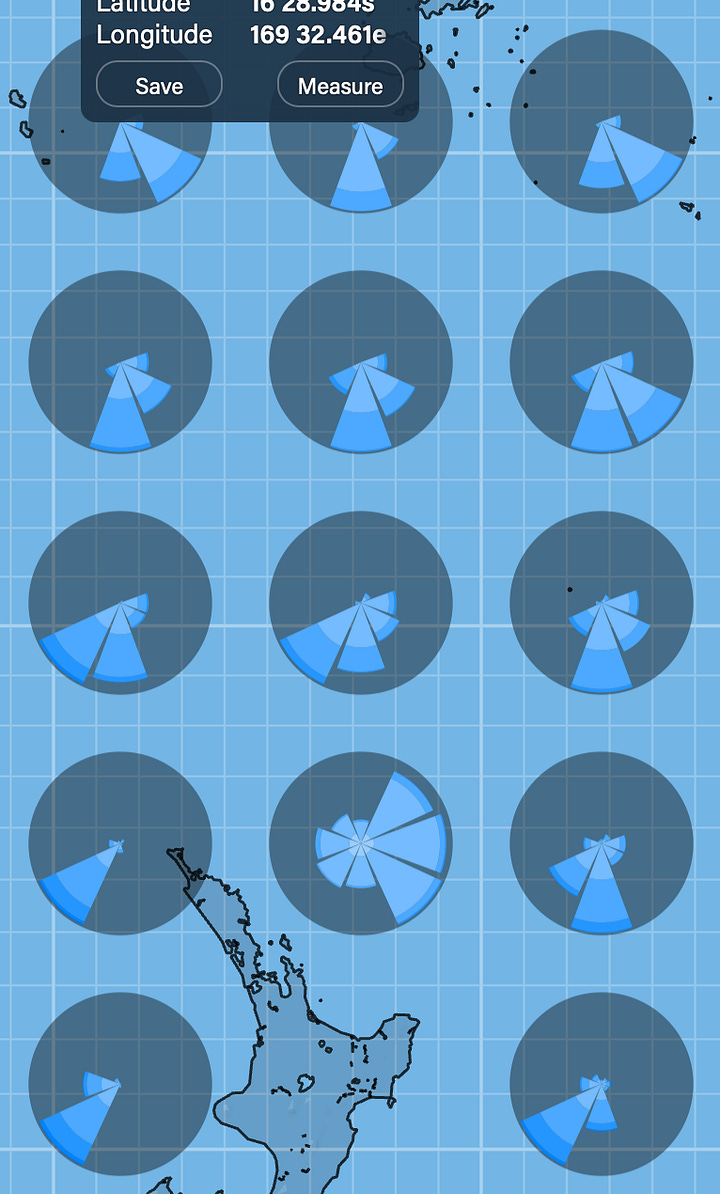

In this example, we have 3-meter seas on a relatively short period on the second day. Not great. 2.5 meters or less on a long period is better. The wave “period” is the distance between the waves in seconds. 2x the height of the wave (in meters) is the minimum. 2.5x is better. A 3-meter wave needs at least a 6-second period. 8 seconds would be better—especially if you are sailing into the seas, which has the effect of shortening the period.

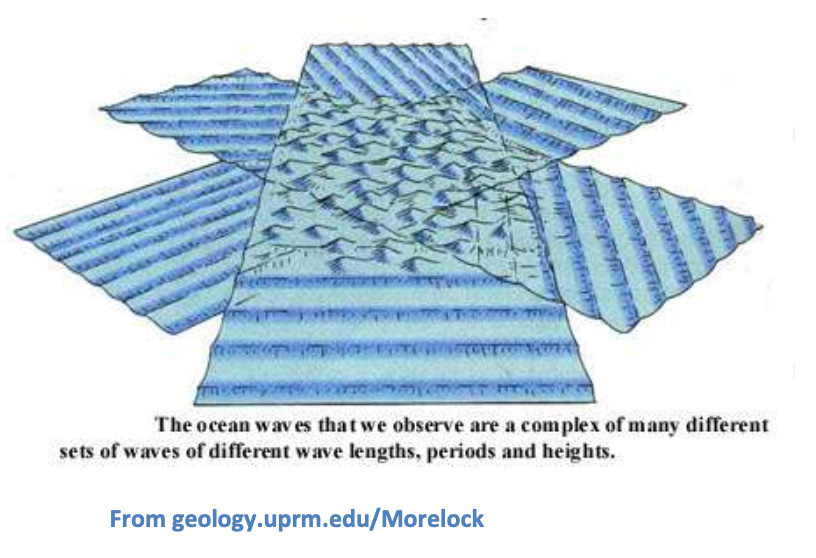

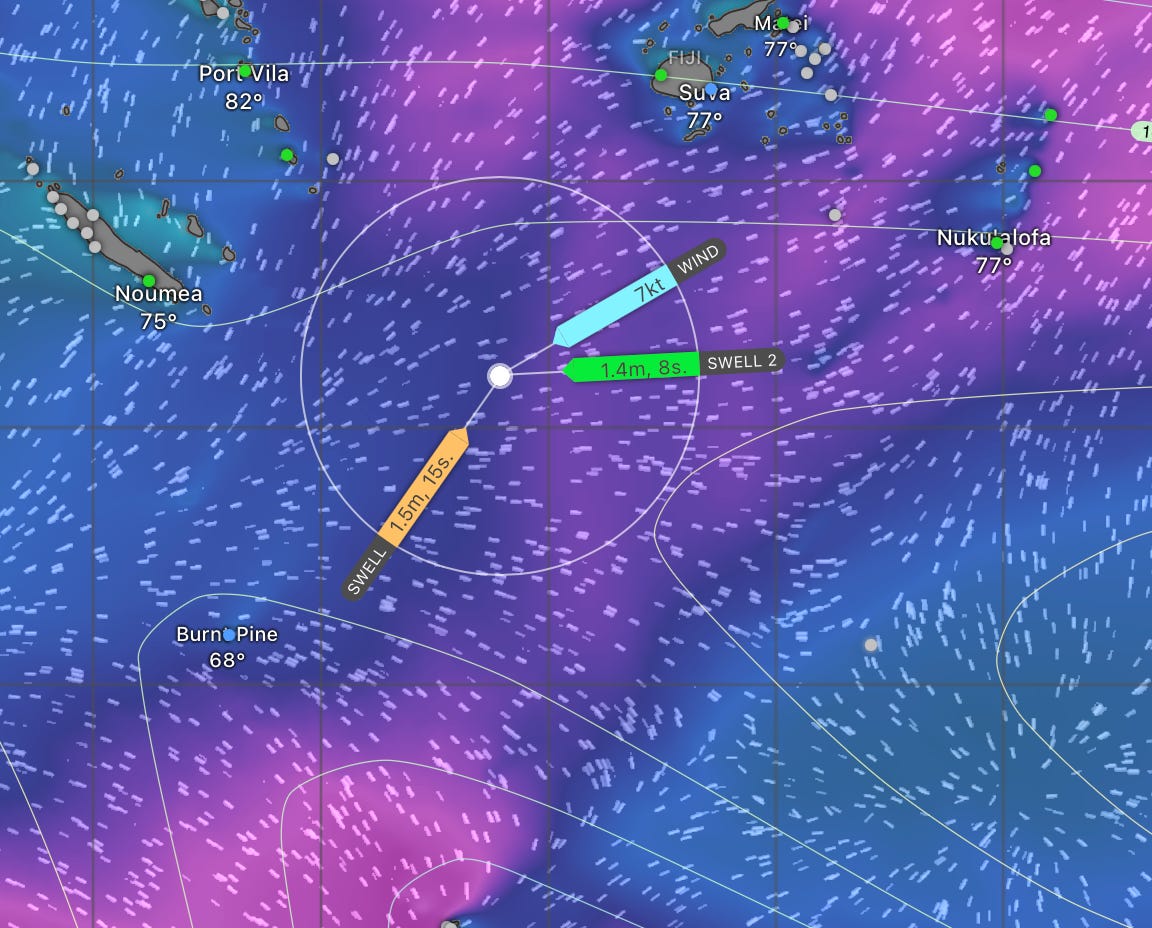

Why The Seas Always Seem Confused

The seas we sail in are made up of several wave trains coming together at once. The dominant swell is from the south (from the storms in the Southern Ocean). The wind is usually from the east (and thus the wind waves are from the east). Often there are leftover wind waves from a different direction as well. They mash up together to create a kind of “lumpy gravy” at best and a “washing machine” at worst.

Weather Routers

I also enlist the help of a few experts—“weather routers”3. They know these patterns better than I ever will. And they are very patient with my questions. I like to work out a route and a strategy, and then have them critique it and challenge my thinking. I find that’s a good way to learn.

Our main routing tool is PredictWind. It’s made by very smart software engineer sailors in New Zealand. The software knows how we sail our boat. It knows our potential. It knows the weather4. And, it knows where we start and finish. It picks the best day and time to leave. It figures out the optimum route to sail, how to configure the boat, and what we can expect on the passage. It updates all of this twice a day. It’s amazing. It has its limitations, but it generally does a great job.

Make a plan but be willing to change your mind

Last year, my friend Viki5 launched from Fiji and got 100 miles down the track when the forecast changed. It no longer looked like good conditions for landfall in New Zealand a week out. She turned around and sailed back to Fiji and waited a week for a better forecast. Subsequently, she had a great sail. That takes enormous patience (and courage). It is very easy to get locked into your plan and ignore new evidence to the contrary. Not all the boats in her departure group turned around. Some boats continued and got promptly smacked by terrible weather as they arrived.

The good news is that I don’t have to decide today because we can’t leave yet. I have a work trip next week. Our crew, my friends Richard and Dave, won’t arrive until the 18th. I play these planning games every morning. I’m trying to be a little less wrong each time.

More on Weather Routing

Tropical Maritime ➜ Subtropical Transition ➜ Temperate Maritime. It’s a classic “gateway” passage from the tropics to mid-latitudes, requiring both tropical seamanship and cold-weather readiness

This year we are working with MetBob again who routed us across the Pacific from Mexico. And, John Martin of Ocean Tactics who routed many of our friends last year.

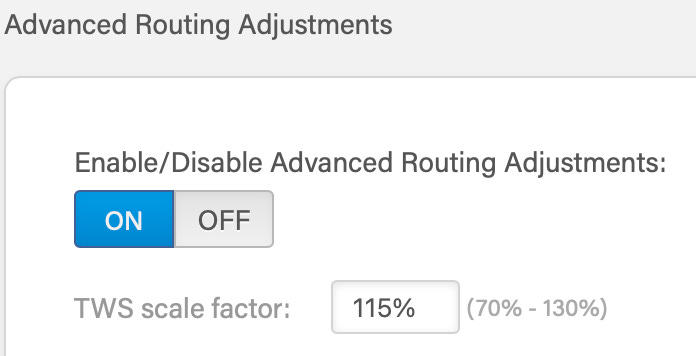

I took Stan Honey’s advice and “scaled up” the forecasted wind speeds using the “TWS Scale Factor” in PredictWind. 115% for the tropics (120% for the mid-latitudes). Wind is forecasted at a 10 meter hight off the surface. Our wind measuring unit is at the top of our mast, 20 meters up. The wind is stronger at 20 meters than at 10 meters. The scaling factor matches the forecast to what our instruments read.

Viki is a bad-ass sailor. She runs www.islandcruising.nz which hosts the largest sailing rallies in the South Pacific. She also publishes Cruise News magazine. If you are sailing around here she is the lady to know.

Looking forward to highlights of the voyage ,

We'll be reading this one next year for sure. Though in our case, it's highly unlikely we'll escape without a gale or storm of one sort or another; the trick will be avoiding getting creamed twice.