Land Ho: New Zealand

Fiji to New Zealand: Passage as Planned, Weather as Forecast (sort of)

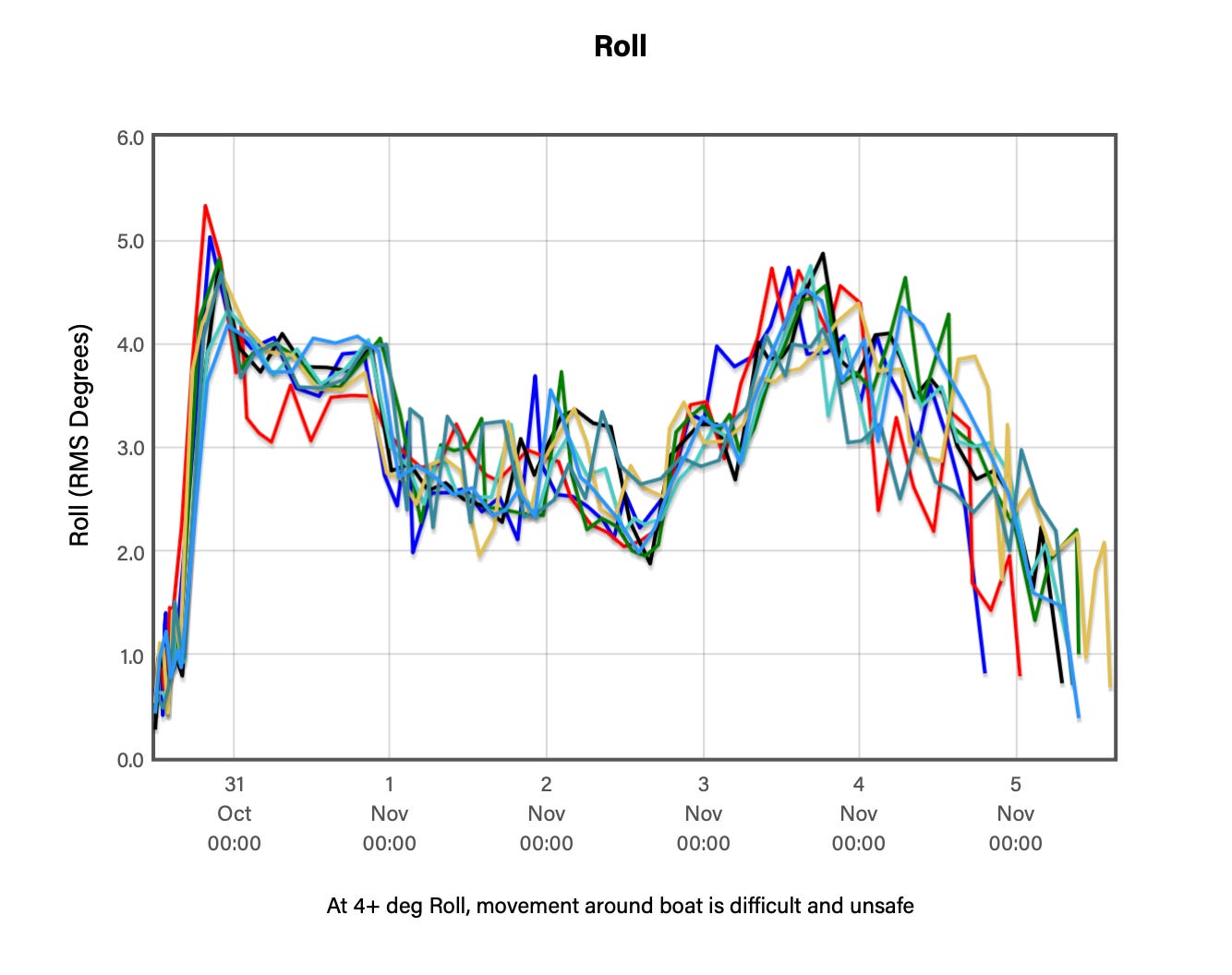

This was the most challenging ocean passage I’ve ever done. Not the longest. Not the worst weather. Not the most boat problems. It was timing the weather window and the variety of conditions that come with crossing three separate climate zones1.

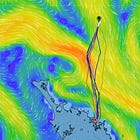

Passage as planned. Weather as forecast. Well, almost as forecast. We encountered an unexpected batch of embedded thunderstorms in the middle of the trip. But otherwise, it was exactly as we, our routing software, and expert weather pros predicted.

It took us five days and 16 hours to make the 1,100nm trip. Compare that to what our routing software predicted—a range from five and a half to six days. Amazingly accurate. Especially given the complexity of the weather systems we crossed. A fast beam reach nearly the entire way.

I get mildly seasick for the first day or two of an ocean passage. I’m functional. I just don’t feel great. This time, I put on a Scopalomine patch in anticipation of what we knew would be rough conditions the first day and again in the middle of the trip. The side effects of scopalomine are dry mouth, metallic taste, and hallucinations. Lesser of two evils, I guess. I’m not sure it helped. It might have delayed me acclimating to the conditions.

Running with the Big Dogs Cats

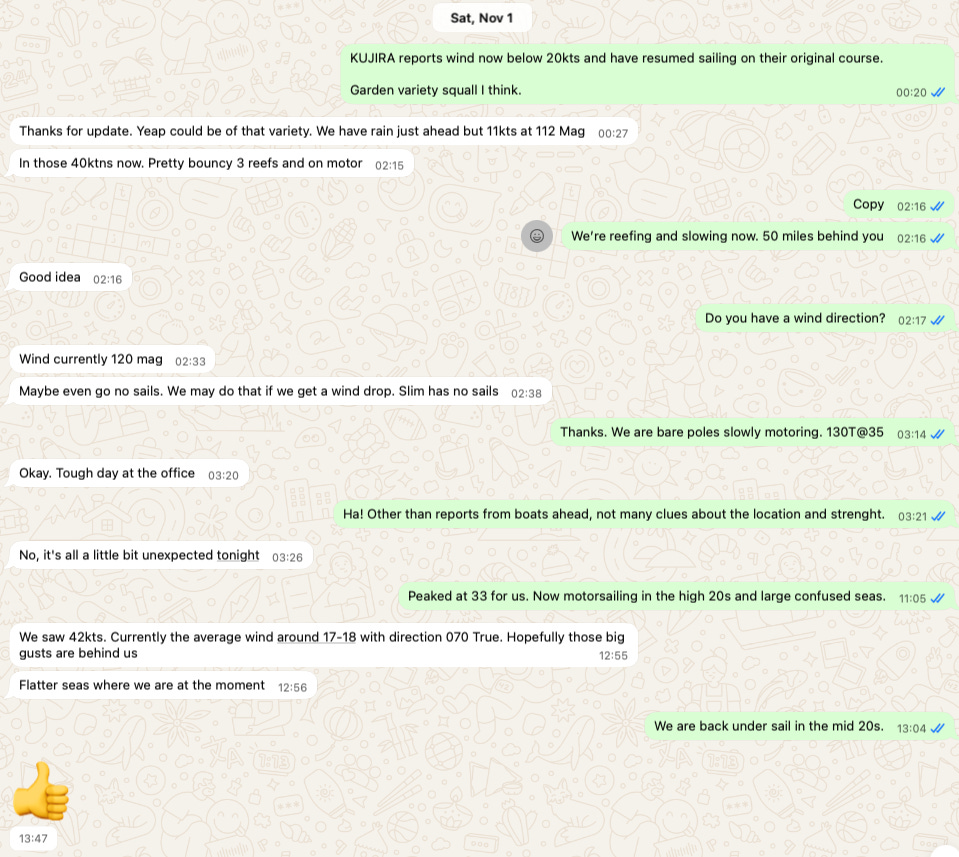

We were sailing along nicely in ten knots of breeze when I got a WhatsApp message from Passage Guardian’s, Peter Mott. “Hi Jim, what wind do you have there?” He went on to alert us that boats ahead of us were running into squalls with strong winds.

We left Fiji with a few large, fast cats. They would make New Zealand a day ahead of us, which meant that they would be running out in front. They served as our forward weather scouts, relaying their conditions back to us as we all sailed south.

The squalls were short-lived—maybe six hours or so. And when they passed, we were back to sailing fast on a beam reach.

Weather Routers

As we often do on these passages, we enlisted the help of two professional weather routers. I like to come up with a plan and then run it past them for their critique and commentary. It’s a good system.

MetBob has been routing us for the last two years, starting with our trip across the Pacific. John Martin of Ocean Tactics is a popular choice amongst the cruisers here and we subscribed to him for this trip as well.

We rely on their input when evaluating the weather window and our target departure day. Once enroute, we send them our position once a day and they reply with anything they see in the forecast I might have missed. And, sometimes they’ll advise a course change to take advantage of favorable current or winds. A team effort.

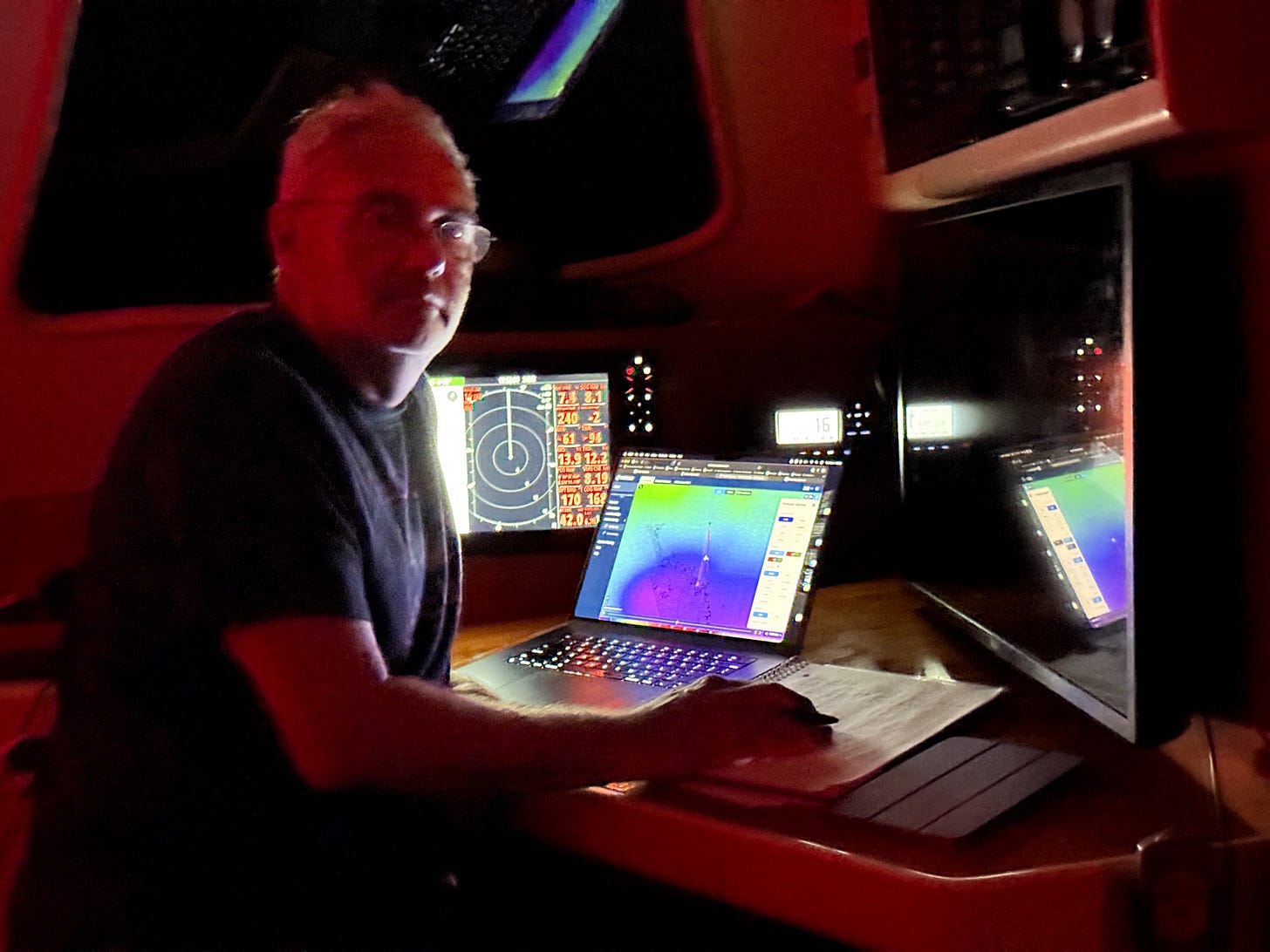

This was our first passages using the new “AI-based” weather models2. I was impressed with their accuracy. They are probabalistic in nature as opposed to the deterministic numerical models we’ve been using. Combined, they give you a good sense of what to expect and how to prepare.

A Great Crew

This was the first passage without Pam. She went home to look after her family and our vacant house. Sailing together these past three years has brought us close together. We gravitate to our strengths: Pam looking after the welfare of the crew; me looking after the welfare of the boat. On a passage we catnap during the day. At night we each stand rotating, three-hour watches. We make a good team.

All of this isn’t to say I didn’t have a great crew aboard for this trip. I did. Richard and Dave were ideal. They put their lives on hold to come to Fiji and make this happen.

Richard stepped into the role of shipkeeping and care and feeding of the crew. He made sure we ate. Dave and I focused on navigating and running the boat. We all stood four-hour watches. Those are long watches, but they give each person a full eight hours off watch. Sleep is a secret weapon on the ocean.

Richard is an ocean sailing veteran. He has a lot of miles in the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of America3. We’ve done a few passages together back when I lived on the Gulf Coast.

Dave is relatively new to ocean sailing, having done a “Baja Bash”4 from Cabo San Lucas to San Diego. He is the consummate outdoorsman. A true McGyver. The guy you want on your side during the zombie apocalypse. He immediately adapted to ocean sailing.

I’ve known these guys for many years. Dave got me into aviation. We worked together back in the mid-90s. He is the quintessential adventurer (and thus this particular adventure). I met Richard in my impressionable 20s when we were slip neighbors on Lake Ponchartrain near New Orleans. We sailed together all over the Gulf Coast.

Ocean sailing is fun and challenging. It’s full of highs and lows (physically, emotionally, and meteorologically). When the passage is over, you mostly remember the people and the experience of sailing together.

Welcome to New Zealand

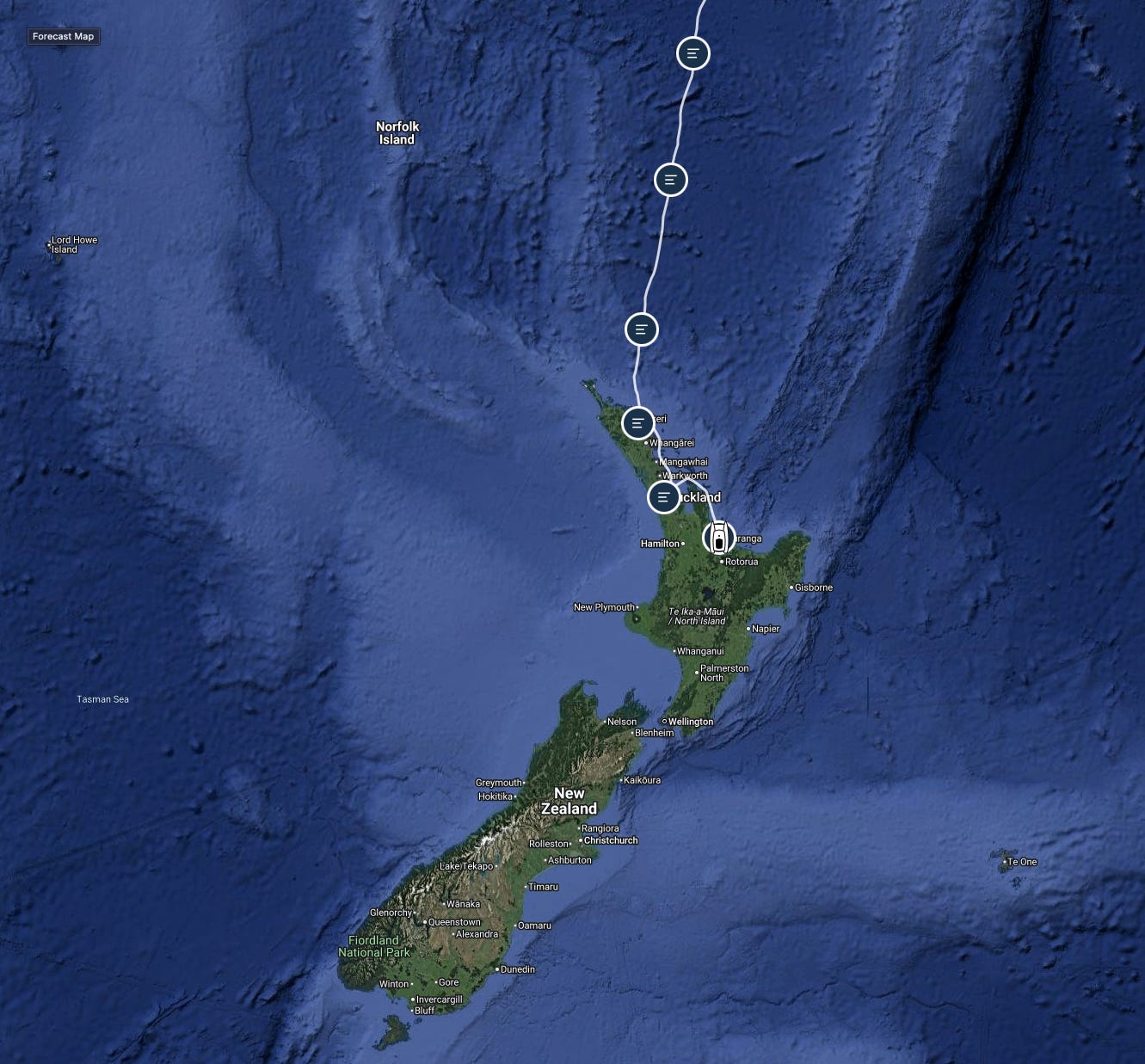

We made landfall on the north end of New Zealand’s North Island. Opua is the closest port of entry to Fiji. My general strategy is to get off the ocean as fast as possible on these trips. Opua fit that bill.

Opua and the Bay of Islands Marina are well equipped for the surge of transient yachts visiting New Zealand this time of year. We arrived in the middle of the night and slowly motored through the dense fog into the Bay of Islands and up the river to Opua. Most of the time, we stand off and wait for daylight when arriving at an unfamiliar harbor. But I’d been here before, and the harbor is well charted, well marked, and well lit. I wasn’t prepared for the thick advection fog that set in as we motored into the bay.

We slowly picked our way in using the radar image overlaid on the electronic chart. By 4am we were tied up to the “Q-Dock.” A hot shower and a nap. Then, the day-long process of getting cleared into the country. Customs, immigration, and biosecurity. All very friendly.

As we were tying up, I went to step off onto the dock and promptly fell into the water. The combination of fatigue, adrenaline withdrawal, and “land sickness” where after a long ocean passage standing on the land causes disorientation. It was a cold shock.

New Zealand insists visiting yachts have a clean bottom free of invasive species. We always scrub our hulls before leaving a country. Our strategy is to leave the bio-fouling where we found it.

New Zealand wants you to submit photographic and video evidence of your clean bottom in advance of your departure from Fiji. Our video was rejected as “inconclusive.” They couldn’t see the hulls well enough. When the bio-security lady came aboard in New Zealand and inspected the boat, she and I sat at my laptop and reviewed the video. She was satisfied that we were clean and, after inspecting the anchor chain and seizing most of our food, signed us off. We were officially cleared into the country.

Down the Coast

We spent a day in Opua catching up with friends, cleaning the boat, doing laundry, and fixing a few things we broke. The weather looked good. We decided to take advantage of it and head down the coast to Auckland. Richard had been aboard for nearly a month. He and Dave both needed to get home and tend to their respective businesses.

I’d always wanted to tie up my own boat in downtown Auckland’s famous Viaduct Harbour. This was my chance. We enjoyed a beautiful day in the City of Sails after our foggy arrival. Richard and Dave booked their flights home. After an amazing dinner at Chef Al Brown’s Depot Eatery, they were off, and I was again solo.

I still needed to get the boat another 100 miles further south to Tauranga, where we planned to haul out and leave the boat. Fortunately, our friend Mikayla, whom we met in the Cook Islands, has a flexible work schedule. She was able to take a day off from teaching and help me make the overnight sail.

My quick trip down the coast was a sampler of what’s here. I was glad to get the boat where we needed it in time for a work trip. But I realized why Kiwi sailors love it here. There are countless anchorages and towns to enjoy. I’m looking forward to our return when we can slow down, head north, and enjoy all of the anchorages we blew past.

End of the Line

We’ve reached the end of the “coconut milk run.” The route following the tradewinds from North America, through the South Pacific Islands to New Zealand. French Polynesia, Cook Islands, Niue, Tonga, Fiji, and NZ. A long-held goal. Two years and over 10,000 nautical miles.

The boat is out of the water and in the capable hands of Tauranga Marina Boatyard and the talented boatbuilders and craftsmen now aboard refitting and remodeling her.

We’re back in the US for a few months to spend time with our families over the holidays. And, we’ll tend to our slowly deteriorating house, which needs some love.

As always, our plans are loose. We expect to be back in New Zealand in February to inspect all the work being done and put the boat back in the water. Then we’ll enjoy some time sailing around New Zealand. Maybe we’ll join friends on the South Island Rally.

The cyclone season in the South Pacific ends May first. We may head back up to Fiji for another season there. Beyond that, who knows? Maybe Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Australia? Maybe back to New Zealand?

Plans written in the sand at low tide.

A Few Photos:

From the Ship’s Log:

Tropical Maritime ➜ Subtropical Transition ➜ Temperate Maritime. It’s a classic “gateway” passage from the tropics to mid-latitudes, requiring both tropical seamanship and cold-weather readiness

The tradional numerical modles like ECMWF, GFS, PWE, and PWG are deterministic. That is they are mathamatical algorithms that produce a single result. A set of predicted conditions in a format called GRIB (for Gridded, Binary). AI models are different (AiFS, and PWAi in this case). They are probabalistic. You feed them the starting conditions just as you do the deterministic models. But instead of running the algorithm, these AI models look back on historical weather and match that up with the starting conditions and use that to produce a forecast. Nobody is exactly sure how they work, but that’s what they do. And the results validate very well with the actual conditions—especially over the medium term which is what we rely on for risk management on an ocean passage.

Formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico.

The great writer and former publisher of Latitude 38 magazine, Richard Spindler coined this term describing the (normally) unpleasant motor trip north into the wind and waves from Cabo to San Diego. Boats “bash” into the seas and prevailing wind which run from north to south.

Such a great read! Also I've just learned that Lake Pontchartrain is not just an emo song that my sister used to listed to, but is a real place: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hu7lIGLchnQ

Thanks for sharing your adventures! Hope there’s more next year!