Why is our solar production low? Why is the weather unpredictable? Why is the sea-state rough and confused? Why so much rain? Over the past two months, I noticed things had changed from what we experienced the previous year.

It’s the dangerous middle1. The term given to the 1,400nm stretch of ocean between French Polynesia’s Society Islands and Fiji. “Middle” because it’s roughly the middle portion of the “Coconut Milk Run” route through the South Pacific from the Marquesas to New Zealand.

It’s dangerous not because of piracy. It’s dangerous because of complacency. We were into a comfortable groove in French Polynesia. The weather was good with sunny days and predictable patterns. The navigation was straightforward and well charted. The distances from one stop to the next were manageable. We could get to and from Tahiti and the Tuamotus in one overnight passage. We could pick our travel windows with confidence.

Leaving the Society Islands in April and sailing west marked a significant change. The weather was less predictable. The stops were further apart. There were fewer boats around. We were out of sync with the main cruiser migration and often sailing alone without a buddy boat nearby.

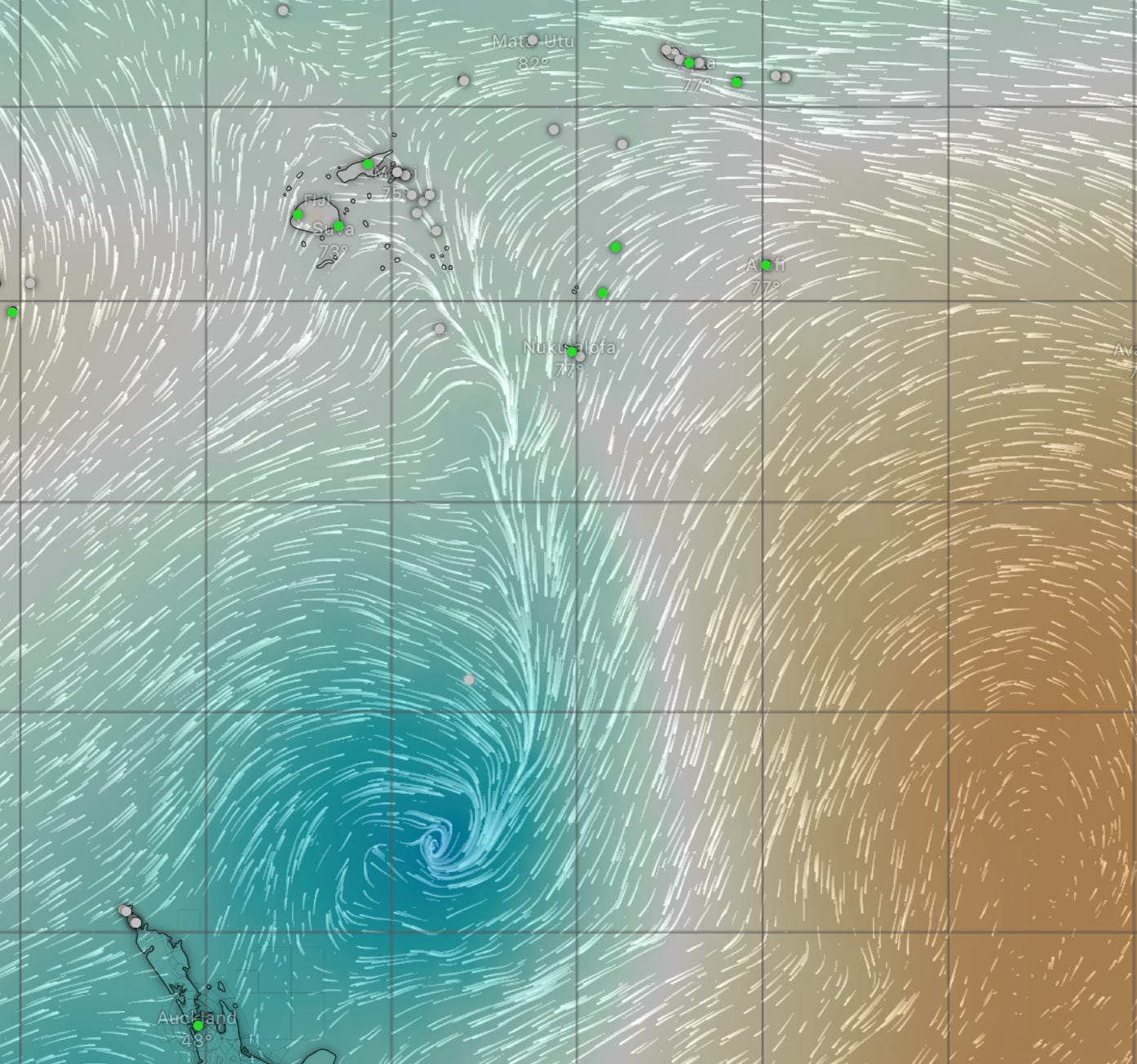

The South Pacific Convergence Zone

The SPCZ2 is an area where the equatorial easterly winds and the southeast trade winds converge. This convergence creates a zone of unstable weather, characterized by erratic trade winds, frequent low-pressure systems, and convergence zone activity. It accounted for the challenging weather, the difficulty in forecasting it, and the resulting drop in solar production. It meant relying on our diesel generator to keep up with our electrical consumption.

Confused Seas

The sea-state is the single most important factor in a passage3. When the seas are calm, anything is possible. When the seas are rough, everything sucks. In this stretch, the seas are “confused”—meaning multiple wave trains of different heights, periods, and directions. The main ocean swell is generated by storms in the Southern Ocean and rolls in from the south. The wind blows mostly from the east to the west and creates wind waves on top of the swell but in an east-to-west direction. The result is at best an annoying “lumpy gravy” sea state or at worst a very rough washing machine that tosses the boat around.

Convergence

Unlike the frontal weather we are accustomed to back home, where weather fronts move predictably from west to east across the weather map, the weather here is dominated by convergence—two air masses crashing into each other and going straight up. Add some atmospheric instability, and you get rain, squalls, thunderstorms, and generally overcast, crappy weather.

South Pacific weather is harder to forecast than weather in the Northern Hemisphere. Weather models need live observations to initialize. There are heaps of live weather observations in the Northern Hemisphere. The models have a lot to work with. The Southern Hemisphere has very few live weather observations. The models have less to work with.

Long Distances

There are a few stops out in the dangerous middle. The Cook Islands, Niue, and Tonga lie on the direct route to Fiji. Some boats sail north to call on American Samoa for easy access to American boat parts and groceries. These stops are far apart. Most are multi-day passages in unpredictable conditions.

The upside is that Aitutaki in the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tonga were more than just way stations. They turned out to be wonderful destinations. I’d be happy going back to all of them. Wonderful people, interesting cultures, beautiful anchorages, and excellent diving.

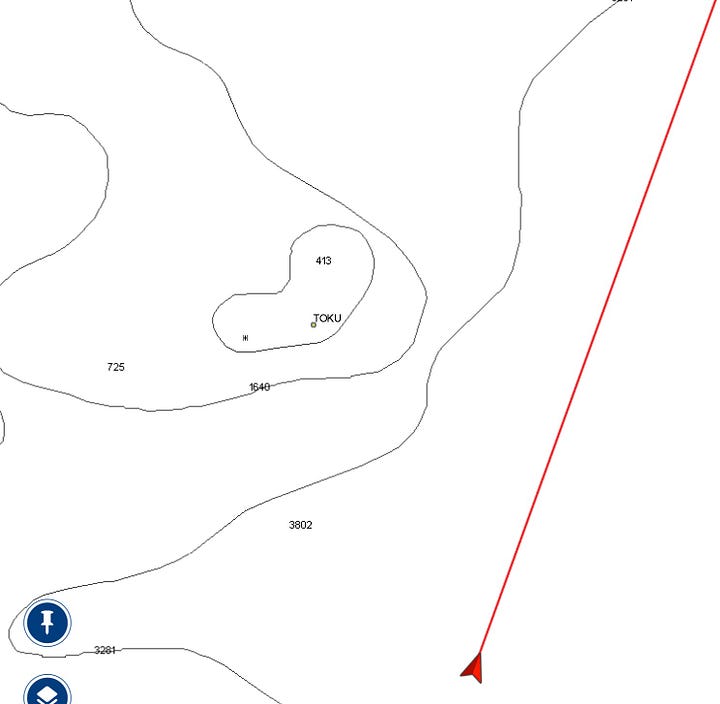

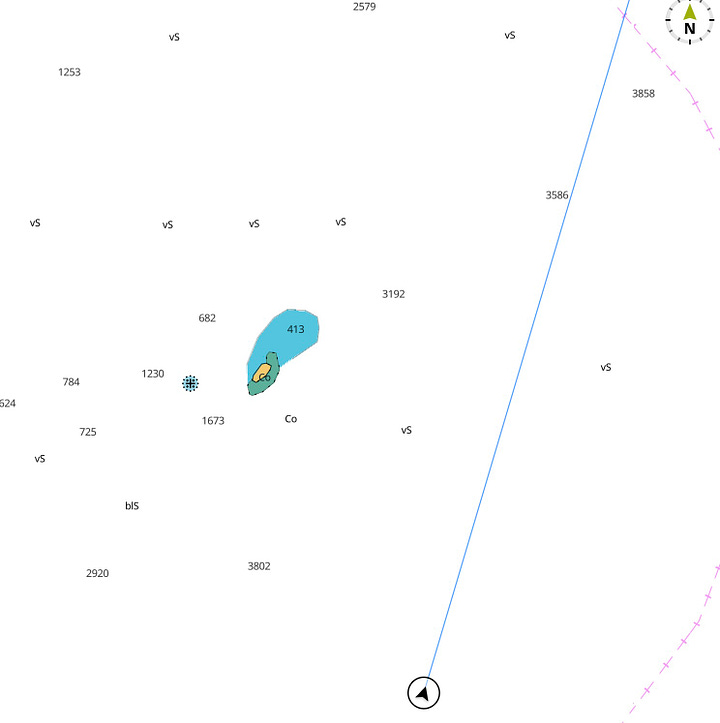

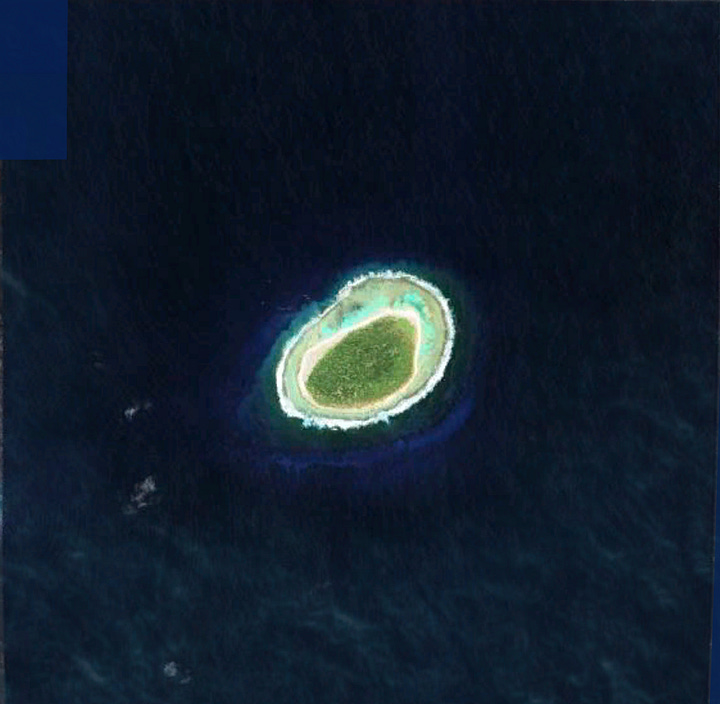

Navigation and Landfall

We increasingly relied on satellite images from Google Earth on this stretch. Nautical charts in this area of the Pacific are often inaccurate. Some are still based on cartography from Captain Cook. There are boats that run up on reefs here either because the reef simply wasn’t on their charts or because they weren’t zoomed in sufficiently on their electronic charts to notice the reef. We use three different chart sources—Navionics (by Garmin), C-Map (by Navico), and New Zealand government charts rendered in OpenCPN. We also use Google Earth satellite images, which are often more accurate than any of the charts.

Fiji

Getting to Fiji was a goal for us this season. Arriving in Fiji means getting here but also continuing another 130nm miles into the country, through the islands and reefs, in order to reach Savusavu, where you can clear customs, immigration, health, and biosecurity. Another half day or more of sailing.

Now that we are here, we’ve had time to rest up and enjoy some luxury time in the new Nawi Island Marina in Savusavu. Reflecting back on the past few months going across the dangerous middle, we didn’t fully appreciate the demands of this part of the South Pacific.

As my friend Chris says, “…this is big-boy sailing…”

Title Image Credit: Edmund1234 - Original sourced from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pacific_Culture_Areas.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=148457632

The term “dangerous middle” was likely coined by Captain John M. Wolstenholme of the British yacht “Mr John VI.” He wrote about it back 2008. I wish I had read his work before we got to this point.

I’m not sure who initially coined the phrase, “South Pacific Convergence Zone.” Our weather router, Bob “MetBob” McDavit, a New Zealand meteorologist, has written about it extensively. https://metbob.wordpress.com/2025/04/28/bob-blog-62/.

New sailors often get hung up on windspeed and wind direction. I did. And the wind does matter. But the sea state matters more. It is the seas that break boats and injure sailors, not the wind. If the wind blows hard enough, long enough the seas will get big.

Insightful and thought provoking. Laura and I are thinking of continuing west, so this is really timely.

Liked from 170 nm due W of Mag Bay