Shakedown

The Adventures of the Sailing Vessel Roam

We enjoyed a successful shakedown sail with our Pacific crossing crew. They took time out of their lives to fly down and go for a three-day sail to test Roam and her new systems. The trip also gave us a chance to test ourselves and see what we might want to add or change to make for a more comfortable and enjoyable trip across the Pacific.

Shakedown

shakedown /shāk′doun″/

noun

1. Extortion of money, as by blackmail.

2. A thorough search of a place or person.

3. A test or period of appraisal followed by adjustments to improve efficiency or functioning.

Many cruisers who make the trek to the South Pacific do it as a crew of two. And while it is something we probably could do, we thought it prudent to bring along an experienced group of sailors whom we know well. A larger crew creates a more social environment with which to share the experience. It also reduces the crew fatigue substantially.

When it is just the two of us on long passages we don't see much of each other because one of us is often asleep. It's been many, many years since we've done a significant passage together. A bigger crew seems like the right decision for us.

The crew includes my brother John who is a long-time sailor, retired Coast Guard officer, navigator, and a formally trained electronics technician. He and I sailed together and raced our J24 in San Francisco when he was stationed in Alameda.

Joan and Mike are our partners from our last boat, Esperanza. Mike and I raced together back in the nineties and we all owned our Catalina 380, Esperanza, together for over 15 years. He and Joan having been sailing, cruising, and racing together most of their adult lives.

Joan and Pam have the unenviable task of planning and provisioning for a crew of five for a month. Think about feeding five people for up to 30 days with limited refrigeration.

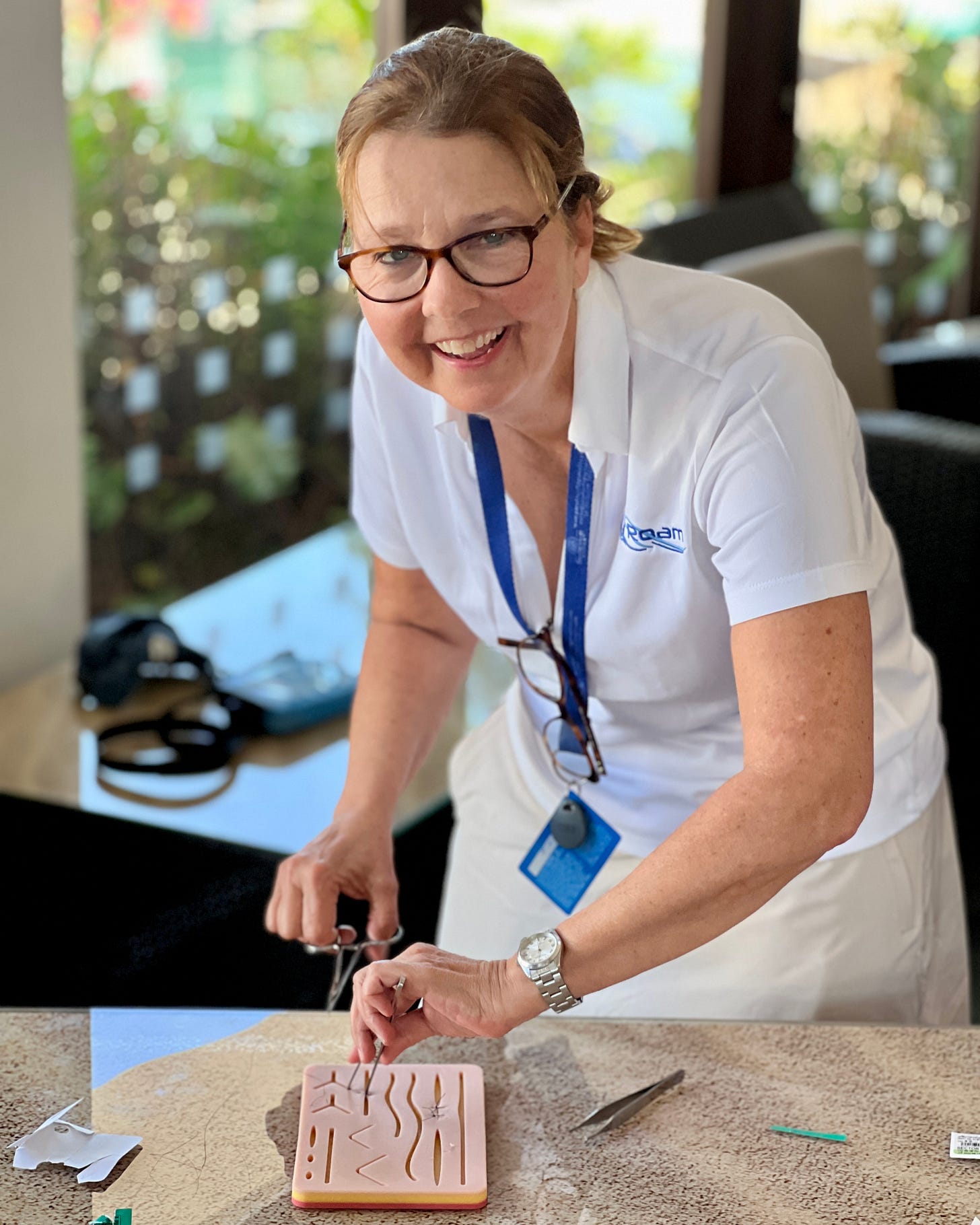

Pam also serves as the ship's medical officer. She's undergone training for the common maladies that occur out on the ocean and at anchor. She has also done an amazing job collaborating with doctors in the US and here in Mexico to assemble our ship's medical kit.

Mike and Joan brought Esperanza here to Paradise Village in Puerto Vallarta a few years ago when we sold our share of her to another friend. It was they who met Roam's former owners and put us all in touch. And now they are heading to the Marquesas with us!

This crew of five will make the passage from Banderas Bay, Mexico to the Marquesas islands in the South Pacific. That is a journey of about 3,000 nautical miles and should take us somewhere between 16 and 20 days depending on the weather. After we make landfall (either Nuku Hiva or Hive Oa) in the Marquesas, they'll sail with us for a bit and then head off to see more of the islands before flying home.

We've made many changes to Roam and her systems. We needed a chance to put them to the test out on the ocean and see what was working and what still needs work. Fortunately, everything work exactly as designed. The boat performed perfectly. And, the crew did great as well! We all learned that going upwind in the ocean in a performance catamaran is a bit like sleeping inside of a freight train.

Once we left the smooth waters of Banderas Bay we bashed upwind for 18 hours to see how both we and the boat would do. Three days gave us a chance to try out our watch keeping system. Mike, John, and I each stand a watch for four hours with eight hours off. For example my watch is 8am to noon and 8pm to midnight.

Joan and Pam are "floaters." They can take a watch if someone needs more rest. They can also team up with the scheduled watch stander for an extra hand. Most of the time they look after the care and feeding of the entire crew.

The most important aspect of any watch keeping system is the amount of contiguous rest a crew member gets. With this system each crew member gets a minimum of eight hours off at a stretch. That's a good chunk of sleep and it worked well during this trial.

The only glitch on the trip happened the final morning as we were reaching south back to Banderas Bay. Mexican fisherman in that area sometimes set long lines out in the ocean. These are often a quarter mile long or longer and often marked only with an occasional empty soda bottle. It's impossible to see these lines if there is any sea running.

The first line we snagged came off easily enough. The second, however got completely wrapped around the boat, the daggerboards, and the rudders. It happened as we turned to avoid it at the last minute. The fisherman to whom the line belonged were nearby and they came back and began cutting us out of the mess. It took nearly two hours with one of the three of them taking our diving mask and diving under the boat to cut away the last of their line from our rudders.

I'm not really sure what the right answer is here. It's hard for me to see it as our fault because these lines are impossible to see and avoid. But I felt bad about them losing the time and having to cut their lines so we tipped them well. How much would you pay someone to save you the hassle of cutting yourself out of a web of fishing line? Exactly!

A Few Photos